By Gerald Sarapu

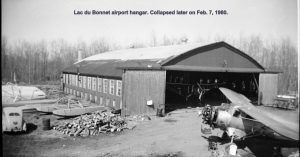

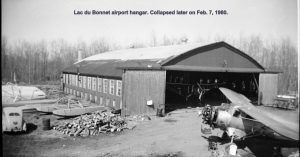

In 1926, the main operational base for aerial photography by the RCAF was transferred from Victoria Beach to Lac du Bonnet. An aerial photograph apparently shows that the hangar was being constructed during the summer of 1928. Yet, another aerial photograph supposedly taken in 1929 shows no evidence of any building. I suppose in the long run the exact date is not important for the purposes of this article.

Circa 1950's

At the time, the primary aircraft were flying boats like the Vickers Viking and Vedettes, so the adjacent runway had not yet been constructed. The clearing for the runway by the base only commenced during 1933, as it was a summer of little activity.

In 1937, operations of the RCAF ceased and the Department of Transport assumed responsibility for the site and presumably the hangar itself. Following WWII, the site was disposed of by Crown Assets.

I do not know, at this time, if and when the old hangar became a separate entity from the adjacent land and runway, but over the years the building had seen numerous occupants such as Central Northern Airways, Transair, AV Air Service and finally Airpark Aviation, which all operated out of the old military structure.

In a letter written to me, senior Aircraft Maintenance Engineer, Rollie Hammerstedt stated: “I first started working there (the Hangar) in 1953. Prior to May 1953, George Fournier, who was the water base engineer in tow, supervised the hangar at changeover period for a few years. Then afterwards Slim Graham was hired by Central Northern Airways (CNA) to take charge of the hangar operation. They designated the operation as Central Maintenance. The duties not only included change overs, but also had a policy of all aircraft serving the bush to be cycled through the Lac du Bonnet hangar every 200 hours of flight time.” He also went on to say that “CNA/Transair, at one time, operated 18 Norseman, plus a couple they took over from Arctic Wings. We usually had 4 Norseman in the hangar at one time. Most years, the back of the hangar was tarped off and heated by a barrel wood stove. We would have three aircraft around the old wooden hoist outside, beside the rail dolly on the ramp. There was a warehouse between the hoist and the water that we used for a few years as a stores department. There was a night watchman on duty seven days a week.” Hammerstedt left Transair in 1961.

On February 7, 1980, the old hangar collapsed. The exact cause is speculative and may or may not be as a direct result of one or more contributing factors. As time passes memories fade, facts are altered and assumptions are created as to the cause of the incident. In any regard, four of the prime factors put forward, as observed by myself as an employee of the company at the time, are as follows:

Factor 1 - Snow loading

Although there was snow on the roof, it was not an abnormal amount of snow in comparison with other years. Snow would have contributed to the overall weight of the structure, but was probably not the singular cause of the failure.

Factor 2 – Bracing cables removed

Originally, the hangar had cables installed along the sides of the building acting as guy-wires. These can be seen in some earlier photographs of the hangar. However, during the previous summer of the collapse, a worker hired for various jobs complained about the difficulties cutting grass with a larger machine around these cables. It was suggested that since all of the cables had no tension on them, and were slack, that they served no useful function and could be removed. The decision was made to cut the cables. A further justification possibly was to better accommodate parking along the side of the building. The worker then proceeded to cut the cables with a cutting torch, but complained that as each strand was cut they unraveled rapidly splattering molten metal everywhere, including on himself. Nothing unusual happened after the cables were cut and that appeared to be the end of that discussion.

Factor 3 – Structural decay

During the previous summer, a new hangar door was being installed. The framework and bracing for this new door was attached to the existing wooden structure of the building. The installation crew observed that there was a significant amount of decay on the vertical rafter supports that ran along the sides of the building. The door was finally installed, but I do not know if the structure of the building was further compromised by the installation.

Factor 4 – The weight of the roof itself

The original roof had been constructed of lumber similar to what is called boxcar siding. To describe the construction: it would be like attaching 2x4 lumber on its flat, tightly spaced, directly onto the rafters over the entire span of the roof. Over the years, it had been patched and resealed several times with additional material layered over top. During demolition after the collapse, it was discovered that on top of the roof lumber was an additional three layers of rolled asphalt roofing and a topped off with a layer of galvanized roofing tin. The weight all added together was significant.

On the day of the collapse the hangar contained three aircraft. A Cessna 337 Skymaster, a Paper PA23-250 Aztec and a Dehavilland DHC3 Otter. During the previous day, the Otter was being readied for an engine removal by myself, the companies Aircraft Maintenance Engineer, and Larry Sarapu, the apprentice. Since I had to make a quick trip into the city the next day, the disconnections for removal were to continue the following day, Friday, by the apprentice himself with the plan to drop it from the aircraft entirely the first thing Monday.

As the apprentice worked by himself, he later said that he kept hearing various noises and frequently looked around to see if anyone else had come into the building. Not seeing anyone and since it was an old building, unheated and not sealed very well, birds often got inside and fluttered around in the rafters, he passed the noises off as that. Having gone as far as he could, he quit early and left for Winnipeg. He did not tell anybody of his plans because nobody else was in that day except for a grader operator hired to clear some snow around the area.

As the grader operator cleaned the taxiway to the main runway, he would make his turnaround in front of the hangar and then continue on back down the taxiway for another pass. Upon returning again, it would be safe to say, he was shocked to see the hangar flattened. In conversation with him later, he was very concerned that he might have accidentally done something to initiate the incident, which of course was in no way the case.

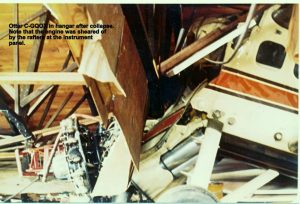

Photo courtesy of Gerald Sarapu

I am not sure of the sequence of events that occurred as the alarm was raised, but I had coincidentally arrived back in Lac du Bonnet and was contacted not long after the collapse. Upon arriving at the scene, it had to be determined if anyone was inside, or should I say, under the rubble. It was known that the apprentice worked that day, but nobody knew he had left early. For that matter, it was unknown if anybody else might have been in the building.

The roof had collapsed so completely in some areas that one could not see under it with a flashlight. To make matters worse, gasoline had leaked out from somewhere and the potential for a fire was a concern. Hydro disconnected the power somewhat easing that concern just a little. One by one everybody that we could think of that might remotely be the inside was accounted for including the apprentice. Other then the authorities securing the area, not much else could be done until daylight the next day.

Commencing the following days, various authorities like the Department of Transport and insurance companies were contacted advising them of the incident and plans were made to extract the aircraft from under the former building.

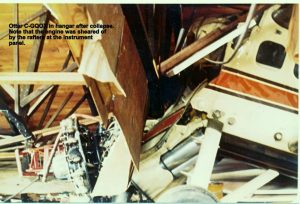

Photo courtesy of Gerald Sarapu

It was decided that the best way to remove the aircraft was to somehow cut the roof into sections and lift it off piece by piece with a hired dragline. First, the outer layer of galvanized sheeting had to be removed and then chainsaws were used to section it up, rolled roofing and all. Cutting through the three layers of the wooden roof with the rolled asphalt roofing still on it, not to mention the nails, quickly dulled the saw blades, but a large quantity of used saw chains were allocated from a local scrap dealer, and with someone continually sharpening as they were replaced, the job was done. The roof sections were extremely heavy and awkward to lift, but finally the first aircraft, the Aztec, was able to be pulled out. It had rafters crushing the cockpit/cabin area and the right wing was crushed, folding the landing gear backwards along with other major damage.

Photo courtesy of Gerald Sarapu

The next aircraft was the Otter, and it had sustained the most damage of the three aircraft. The back of the airplane, at the cabin doors, was crushed so the belly sat on the ground. One wing was crushed to the floor. The engine, that myself and the apprentice were working on, sat on the floor having been sheared off the airframe by a rafter slicing through the cockpit at the pilot’s seat. It is also to be noted, that prior to lifting off the roof, one could see that the rim of one of the main landing gear wheels was sitting on the concrete, thus assuming the tire had popped. Not so. The weight was so great on the airplane that after it was lifted off, the tire resumed its normal shape. I also have one picture of the Otter’s vertical stabilizer penetrating the hangar roof prior to its removal.

The final aircraft to come out was the Cessna 337. It also suffered substantial damage. Probably the most interesting of the damage this aircraft suffered was that the arch of the spring on one of the main landing gear had significantly straightened out. Thus, an indication of the weight that sat on it.

One by one, the aircraft were disposed of by the insurance companies and the rubble from the former hangar cleaned up so that by the end of that summer all that was left was a concrete pad. Today, the property is a private residence, and has been landscaped and treed so there is no evidence that the former military base once existed.