Category Archives: Uncategorized

Pioneer Bush Pilot Norman Cole McCoy 1918-1985

Written by Tim McCoy

Norm McCoy was born in Ontario, Canada on Manitoulin Island in 1918. Son to a ship captain on the Great Lakes, he often worked as a crew member although his main ambition was to follow his older brother’s footsteps and become a commercial pilot.

Looking for employment, Norm ended up in Lac du Bonnet Mb.in 1939 working on aircraft at Starratt Airways where he obtained his Aircraft Maintenance Engineer License. Norm was very fond of Lac du Bonnet and soon met the love of his life Dorothy Elliott, the daughter of George and Emma Elliott, who spent their summers at the Riverland cottage in Lac du Bonnet.

Norm, while working at Starratt Airways, met a second pilot known as “Shorty” Holden, who not only encouraged Norm to become a pilot, but also lent him the money to take flying lessons.

Norm was a natural when it came to flying and most of his flying career was with the Manitoba Government Air Services in Lac du Bonnet. During his career he was stationed in Norway House as well as The Pas where he was Base Superintendent. While flying out of The Pas in winter with little heat in the aircraft he flew many flights up to the frozen north for survey work and Natural Resource Research. During summer months he flew many firefighters and also water bombed forest fires.

Eventually Norm returned to Lac du Bonnet and in 1971 was appointed Director of the Manitoba Government Air Division the position he held until retirement in 1983.

Norm was fortunate enough to have flown a variety of aircraft over the years such as Otters, Turbo Beavers, Standard Beavers, Huskys, and the list goes on. Although navigational aids consisted at the time of a compass and a map Norm flew thousands of hours without incident.

MGAS Pilot Norm McCoy on the float of the aircraft he was flying during the 1950 Red River flood, dropping hay bales to cattle stranded on high ground.

Museum Has Impression on Summer Student

Kaitlyn Mitchell, 2017 Summer Museum Assistant

Throughout the month of July, Kaitlyn gave museum tours and performed a number of office duties including: cataloging multiple donated artifacts, taking pictures of such artifacts and uploading the images onto computer, organizing the Springfield Leader weekly newspaper, making arrowheads and doing craft preparation for Heritage Day. She also did regular cleaning of the museum.

Kaitlyn has noticed that the RM 100 travelling trunks are among the first things visitors look at upon entering the museum. The interactive exhibits, like the wool carder and furs, are also quite popular, and believes another interactive exhibit would encourage more people to attend and enjoy their visit.

Kaitlyn has also suggested that more advertising is needed to inform the public about where the museum is located and when it is open. She lists the public library as a place for museum brochures and, since it is a high traffic area, the Sunova sign for advertisements.

For the month of August, Kaitlyn continued to give museum tours, organize and catalogue artifacts, make arrowheads, and prepare craft materials and posters for Heritage Day.

She has noted that a lot of visitors have commented on how well the museum was constructed and organized, mentioning that their visit was enjoyable.

She also attended the Fire & Water Festival, with a table in Artisan Square. They sold two books, one membership and thirteen bags of wild rice. Overall, the wild rice fundraiser did quite well this month, with a total of twenty-seven bags sold both at the museum and the Fire & Water Festival.

Kaitlyn suggested that a larger sign is needed near the highway to attract more visitors, informing them when the museum is open.

Heritage Day 2017

Kaitlyn believed the Heritage Day was “quite a success.” She noted that the performers were excellent and that the kids’ obstacle course and craft making went really well. A lot of positive comments were received about the event throughout the day. Kaitlyn stated that those in attendance were “very pleased and left with smiles on their faces.”

Travelling Suitcase Exhibit

Kaitlyn created a travelling suitcase exhibit on growing up in the 1950s. She thoroughly researched and planned the case before putting the artifacts, photographs and written information together in the display.

Overall, Kaitlyn believes the museum did well this summer, especially with the Open House, Canada Day and Heritage Day events. She enjoyed all aspects of the job and found it an educational experience. Kaitlyn is incredibly grateful for Terry and Marlene, appreciating the time and hard work given to help her with all aspects of the job. She enjoyed her time at the museum and hopes to apply for the position again next year.

Starratt Airways and Transportation

Starratt Airways and Transportation

Written by Bob Starratt

All photos courtesy of Bob Starratt

Early History

Born in 1887, Robert Wright Starratt grew up in Dorchester, New Brunswick. As a young man, he ventured west in 1910 to Saskatchewan, working with the survey crew for the Grand Truck Pacific Railway. His fiancée, Iris Irving, travelled west in 1913 and they were married that year in Wakaw, Sask. When his work on the railway ended, he joined the Hudson's Bay Company freighting supplies by canoe and small boat during the summer season and horse teams in the winter. His territory encompassed Lac Laronge, Sk in the west to The Pas, Mb in the east, traversing Montreal Lake and navigating the Montreal and Saskatchewan Rivers. Iris travelled back to the east coast by train in 1916 for the birth of their first child, a son named Bud.

Soon, the young family moved further west into the Peace River country of northern Alberta. Bob broke the land and the family homesteaded there until late in 1925. While there, sons Billie, Don and Dean were born into the family. Iris returned to New Brunswick with the four children and Rob gained employment in Winnipeg during the winter, painting a hotel owned by former Peace River neighbour, Jack Grey.

Hudson History

Bob secured employment with the Hudson's Bay Company once again and was sent to Hudson, Ontario in the spring of 1926 to run their transportation interests in the Woman and Confederation Lake areas. There were 7 gold mines in production here before the first mine in Red Lake became operational. In September 1926, Iris and the four children arrived in Hudson. In 1928, Starratt, along with prospectors George and Collin Campbell, formed Northern Transportation(NT). George left the company after only 9 months but would go on to discover the Campbell gold mine in Balmertown. Mining was flourishing in the north and the company used tractor trains in winter and then bought Red Lake Transport and the Lac Seul boats of the Hudson's Bay Company. Collin Campbell, fearing it was all over with the crash of the stock market in October 1929, departed Northern Transportation leaving Starratt as the sole owner.

In 1932, NT acquired a new deHavilland 60M Moth, their first airplane, to keep in contact and monitor the progress of the tractor trains. The first pilot was the legendary bush pilot and early aviation pioneer, Harold Farrington. The company was now an all-season hauler utilizing land, air and water. In 1935, Starratt Airways and Transportation (SAT) was formed and additional aircraft were rapidly acquired. Airplanes were only part of the company with numerous boats and tractors carrying the bulk of the freight. Virtually all of the mining equipment for the Red Lake and Pickle Lake gold zones was hauled from Hudson by plane, boat or tractor train. Very quickly SAT became a dominant player in the transportation industry in Northwest Ontario. In 1939 alone, Starratt airplanes flew 12,604 passengers and 6,583,804 pounds of freight while flying over 1,000,000 airmiles. Boat and tractors hauled another 600 passengers and 34,000,000 pounds of freight. Other major contracts undertaken were a 10,000 cord pulpwood haul to the rail at Sioux Lookout, a late winter equipment haul from the rail at Savant Lake to Pickle Crow and an Ontario Hydro contract to haul cement and other supplies from Ferland on the rail to the Ogoki diversion project.

Starratt initiated the use of marine railways on the three portages between Lac Seul and Red Lake. This allowed fully loaded scows to be shuttled between the lakes rather than being unloaded and transported across portages by horses or people only to be reloaded again and again. Prior to the marine railways, this had to happen three different times before reaching Red Lake and at the tram at Ear Falls. The boat route from Hudson to Red Lake was 184 miles. Use of portages starting right out of Hudson and along the route shortened this considerably for the tractor trains.

Overall SAT had 18 airplanes in service during its 7 year existence. Some burned, some crashed and some were conscripted by the RCAF during WWII. Eight were transferred to the CPR when the company was sold in 1942.

Lac du Bonnet Connection

CF-BGY

Starratt Airways started flying regularly scheduled flights into Manitoba in January 1938 after purchasing a Beechcraft 18 twin engined aircraft, CF-BGY. BGY was the first Beech 18 on skis and floats. Initially, the flights landed at the Winnipeg airport on skis, but because the airplane was equipped with floats in the summer, a water base would have to be established. Discussions with the city of Selkirk resulted in the city constructing a dock to accept the Starratt aircraft. At this time, other airlines servicing the gold fields in NW Ontario, such as Wings Ltd and Canadian Airways, were flying into Lac du Bonnet and transporting their passengers to Winnipeg via taxi, but the Starratt fare to Winnipeg and Selkirk was lower than the others fares to Lac du Bonnet.

Shorty Holden

The Department of Transport ruled that they would allow Starratt Airways to continue to fly into Winnipeg and Selkirk, but they would not approve the lower rate, therefore to remain price competitive Starratt began using LdB as their Manitoba base. The base agent converted a Dodge car into a 7 passenger vehicle by removing the trunk, adding dual rear wheels and a roof baggage rack and made the taxi runs in and out of Winnipeg with this Vehicle. Shorty Holden, later a resident of Lac du Bonnet, was a pilot for Starratt Airways.

Planes at Lac du Bonnet

In 1938, the schedule was Kenora, Red Lake, Winnipeg (Winter) and Kenora, Red Lake, Lac du Bonnet (Summer). In 1939 the route was expanded and BGY was based in Hudson instead of Kenora. All days of the week but Sunday, BGY piloted by Hump Madden would fly Hudson-Sioux Lookout-Uchi Lake-Red Lake-Lac du Bonnet and returned to Hudson by the same route.

In 1940, the route expanded again and during that year Hump Madden joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and was replaced by Bud Starratt, son of the owner Robert W Starratt. Pickle Lake was added to the route and the sched became Hudson-Sioux Lookout-Pickle Lake-back to Sioux Lookout-Uchi Lake-Red Lake-Lac du Bonnet. If one of the locations on the route did not have any passengers any given day it would be bypassed.

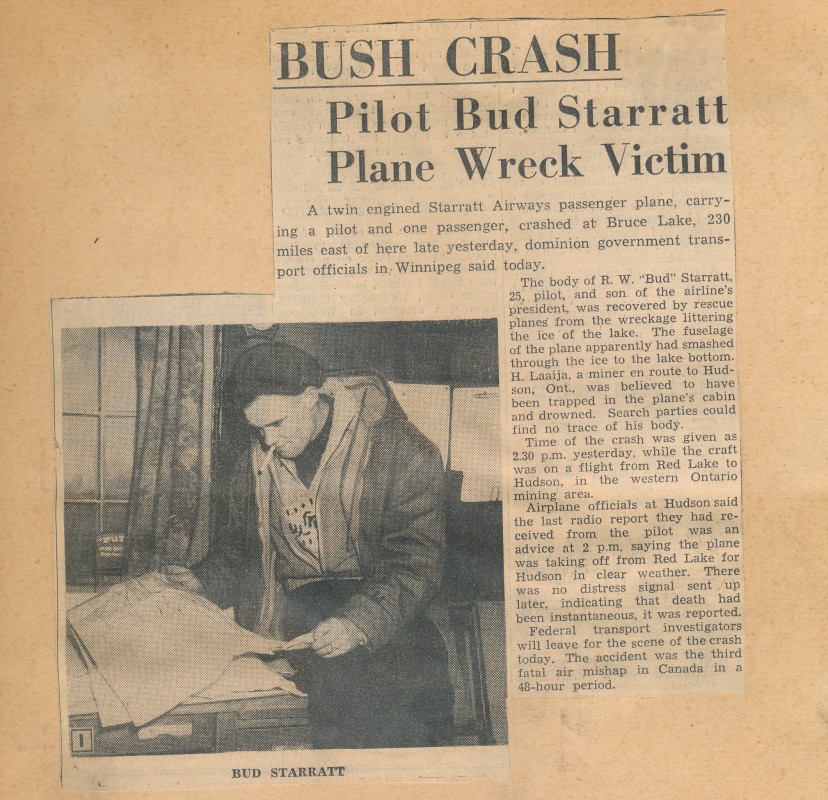

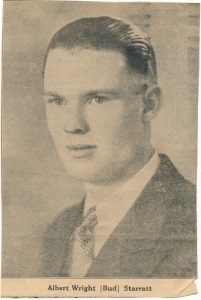

Bud Starratt

Tragically in January 1941, on the return flight from Lac du Bonnet via Red Lake, Bud Starratt was overcome by carbon monoxide poisoning and BGY crashed onto the ice on Bruce Lake near Ear Falls. Bud and the lone passenger were killed, the only fatalities ever suffered by the airline. Starratt Airways rented another Beech 18, CF-BQG, and continued to fly into Lac du Bonnet until the company was sold to Canadian Pacific Railways. The name Starratt Airways was used by CPR for a few years and then along with similar feeder airlines in the country were eventually joined together to form Canadian Pacific Airlines, Canada's second national airline.

Starratt The Man

RW Starratt was a very benevolent person while living in Hudson. Missionaries of all denominations were flown free of charge to do their ministering. Trappers and miners were looked in on by air and toys were delivered gratis to Indian Reserves and isolated communities. In 1939, 72 school children and their chaperones from Red Lake were barged from Red Lake, over the portages and then the length of Lac Seul to meet the King and Queen at the railway station in Sioux Lookout, during the Royal Tour. He flew the Red Lake Wanderers hockey team to Port Arthur to compete in the semi-final of the Allen Cup without charge. During World War II, RW worked as a dollar a year man overseeing the national scrap metal collection program for the war effort.

Robert W. Starratt, middle

After he left Hudson in 1942, he owned lumber mills in Spurfield, Alberta and then for many years the Canyon Creek Sawmill in Valemount, BC. He wintered in Hollywood, Florida and spent the summers in Valemount. In 1967, he passed away in Florida at the age of 80. If you are travelling highway 16 west of Jasper and through Valemount you will see a sign on the highway at the west end of town stating "Robert W Starratt Wildlife Sanctuary." After Starratt’s death, his sons Don and Dean donated 600 acres of Bob Starratt's wetland property to the British Columbia government at this site.

Robert Starratt and his first wife Iris, along with the remains of his sons Bud and Billie (killed as a teen in a shooting accident), are interred in the Elmwood Cemetery in Winnipeg.

The photos below are from Tim McCoy Collection.

They depict the January 1941 crash of BGY.

Hangar Collapse at Lac du Bonnet

By Gerald Sarapu

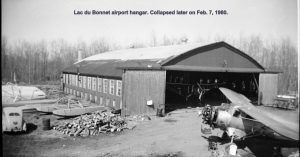

In 1926, the main operational base for aerial photography by the RCAF was transferred from Victoria Beach to Lac du Bonnet. An aerial photograph apparently shows that the hangar was being constructed during the summer of 1928. Yet, another aerial photograph supposedly taken in 1929 shows no evidence of any building. I suppose in the long run the exact date is not important for the purposes of this article.

Circa 1950's

At the time, the primary aircraft were flying boats like the Vickers Viking and Vedettes, so the adjacent runway had not yet been constructed. The clearing for the runway by the base only commenced during 1933, as it was a summer of little activity.

In 1937, operations of the RCAF ceased and the Department of Transport assumed responsibility for the site and presumably the hangar itself. Following WWII, the site was disposed of by Crown Assets.

I do not know, at this time, if and when the old hangar became a separate entity from the adjacent land and runway, but over the years the building had seen numerous occupants such as Central Northern Airways, Transair, AV Air Service and finally Airpark Aviation, which all operated out of the old military structure.

In a letter written to me, senior Aircraft Maintenance Engineer, Rollie Hammerstedt stated: “I first started working there (the Hangar) in 1953. Prior to May 1953, George Fournier, who was the water base engineer in tow, supervised the hangar at changeover period for a few years. Then afterwards Slim Graham was hired by Central Northern Airways (CNA) to take charge of the hangar operation. They designated the operation as Central Maintenance. The duties not only included change overs, but also had a policy of all aircraft serving the bush to be cycled through the Lac du Bonnet hangar every 200 hours of flight time.” He also went on to say that “CNA/Transair, at one time, operated 18 Norseman, plus a couple they took over from Arctic Wings. We usually had 4 Norseman in the hangar at one time. Most years, the back of the hangar was tarped off and heated by a barrel wood stove. We would have three aircraft around the old wooden hoist outside, beside the rail dolly on the ramp. There was a warehouse between the hoist and the water that we used for a few years as a stores department. There was a night watchman on duty seven days a week.” Hammerstedt left Transair in 1961.

On February 7, 1980, the old hangar collapsed. The exact cause is speculative and may or may not be as a direct result of one or more contributing factors. As time passes memories fade, facts are altered and assumptions are created as to the cause of the incident. In any regard, four of the prime factors put forward, as observed by myself as an employee of the company at the time, are as follows:

Factor 1 - Snow loading

Although there was snow on the roof, it was not an abnormal amount of snow in comparison with other years. Snow would have contributed to the overall weight of the structure, but was probably not the singular cause of the failure.

Factor 2 – Bracing cables removed

Originally, the hangar had cables installed along the sides of the building acting as guy-wires. These can be seen in some earlier photographs of the hangar. However, during the previous summer of the collapse, a worker hired for various jobs complained about the difficulties cutting grass with a larger machine around these cables. It was suggested that since all of the cables had no tension on them, and were slack, that they served no useful function and could be removed. The decision was made to cut the cables. A further justification possibly was to better accommodate parking along the side of the building. The worker then proceeded to cut the cables with a cutting torch, but complained that as each strand was cut they unraveled rapidly splattering molten metal everywhere, including on himself. Nothing unusual happened after the cables were cut and that appeared to be the end of that discussion.

Factor 3 – Structural decay

During the previous summer, a new hangar door was being installed. The framework and bracing for this new door was attached to the existing wooden structure of the building. The installation crew observed that there was a significant amount of decay on the vertical rafter supports that ran along the sides of the building. The door was finally installed, but I do not know if the structure of the building was further compromised by the installation.

Factor 4 – The weight of the roof itself

The original roof had been constructed of lumber similar to what is called boxcar siding. To describe the construction: it would be like attaching 2x4 lumber on its flat, tightly spaced, directly onto the rafters over the entire span of the roof. Over the years, it had been patched and resealed several times with additional material layered over top. During demolition after the collapse, it was discovered that on top of the roof lumber was an additional three layers of rolled asphalt roofing and a topped off with a layer of galvanized roofing tin. The weight all added together was significant.

On the day of the collapse the hangar contained three aircraft. A Cessna 337 Skymaster, a Paper PA23-250 Aztec and a Dehavilland DHC3 Otter. During the previous day, the Otter was being readied for an engine removal by myself, the companies Aircraft Maintenance Engineer, and Larry Sarapu, the apprentice. Since I had to make a quick trip into the city the next day, the disconnections for removal were to continue the following day, Friday, by the apprentice himself with the plan to drop it from the aircraft entirely the first thing Monday.

As the apprentice worked by himself, he later said that he kept hearing various noises and frequently looked around to see if anyone else had come into the building. Not seeing anyone and since it was an old building, unheated and not sealed very well, birds often got inside and fluttered around in the rafters, he passed the noises off as that. Having gone as far as he could, he quit early and left for Winnipeg. He did not tell anybody of his plans because nobody else was in that day except for a grader operator hired to clear some snow around the area.

As the grader operator cleaned the taxiway to the main runway, he would make his turnaround in front of the hangar and then continue on back down the taxiway for another pass. Upon returning again, it would be safe to say, he was shocked to see the hangar flattened. In conversation with him later, he was very concerned that he might have accidentally done something to initiate the incident, which of course was in no way the case.

Photo courtesy of Gerald Sarapu

I am not sure of the sequence of events that occurred as the alarm was raised, but I had coincidentally arrived back in Lac du Bonnet and was contacted not long after the collapse. Upon arriving at the scene, it had to be determined if anyone was inside, or should I say, under the rubble. It was known that the apprentice worked that day, but nobody knew he had left early. For that matter, it was unknown if anybody else might have been in the building.

The roof had collapsed so completely in some areas that one could not see under it with a flashlight. To make matters worse, gasoline had leaked out from somewhere and the potential for a fire was a concern. Hydro disconnected the power somewhat easing that concern just a little. One by one everybody that we could think of that might remotely be the inside was accounted for including the apprentice. Other then the authorities securing the area, not much else could be done until daylight the next day.

Commencing the following days, various authorities like the Department of Transport and insurance companies were contacted advising them of the incident and plans were made to extract the aircraft from under the former building.

Photo courtesy of Gerald Sarapu

It was decided that the best way to remove the aircraft was to somehow cut the roof into sections and lift it off piece by piece with a hired dragline. First, the outer layer of galvanized sheeting had to be removed and then chainsaws were used to section it up, rolled roofing and all. Cutting through the three layers of the wooden roof with the rolled asphalt roofing still on it, not to mention the nails, quickly dulled the saw blades, but a large quantity of used saw chains were allocated from a local scrap dealer, and with someone continually sharpening as they were replaced, the job was done. The roof sections were extremely heavy and awkward to lift, but finally the first aircraft, the Aztec, was able to be pulled out. It had rafters crushing the cockpit/cabin area and the right wing was crushed, folding the landing gear backwards along with other major damage.

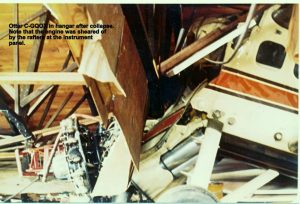

Photo courtesy of Gerald Sarapu

The next aircraft was the Otter, and it had sustained the most damage of the three aircraft. The back of the airplane, at the cabin doors, was crushed so the belly sat on the ground. One wing was crushed to the floor. The engine, that myself and the apprentice were working on, sat on the floor having been sheared off the airframe by a rafter slicing through the cockpit at the pilot’s seat. It is also to be noted, that prior to lifting off the roof, one could see that the rim of one of the main landing gear wheels was sitting on the concrete, thus assuming the tire had popped. Not so. The weight was so great on the airplane that after it was lifted off, the tire resumed its normal shape. I also have one picture of the Otter’s vertical stabilizer penetrating the hangar roof prior to its removal.

The final aircraft to come out was the Cessna 337. It also suffered substantial damage. Probably the most interesting of the damage this aircraft suffered was that the arch of the spring on one of the main landing gear had significantly straightened out. Thus, an indication of the weight that sat on it.

One by one, the aircraft were disposed of by the insurance companies and the rubble from the former hangar cleaned up so that by the end of that summer all that was left was a concrete pad. Today, the property is a private residence, and has been landscaped and treed so there is no evidence that the former military base once existed.